I’ve been in this field for a while now. I’ve been to a number of conferences over the years. I read lots of magazines and blogs. Over the years, I’ve seen lots of industry professionals commenting on the current state of our industry. From the quality of design, to the tools we use, to the data we collect… there are lots of experts sharing opinions with the community about things we as an industry are doing wrong. While expressing their concerns, they often will share examples of best practices, providing an example of the type of work we should be doing. If you’re one of the people who are participating in conversations like this – and there are a growing number of you out there – I have a simple request.

Please stop.

This may seem like a strange request. After all, I’m a huge advocate of sharing and connecting with peers to learn. We need these examples of high-quality practices to give us a benchmark against which to judge our performance. I applaud anyone who shares their work with peers, and I think our industry needs more of this.

For me, the issue starts to shift when there are judgments being made about the work of others. I’ve been involved in countless conversations that consist of experienced professionals looking at a learning program and deciding, essentially, “This is crap”.

For me, the issue starts to shift when there are judgments being made about the work of others. I’ve been involved in countless conversations that consist of experienced professionals looking at a learning program and deciding, essentially, “This is crap”.

To clarify, I don’t have a problem with judging someone else’s work in and of itself. I have a problem when a judgment is made without enough information upon which to make an informed assessment. Let’s explore a few reasons why I think judging without context needs to stop.

The Context of Reality

You simply can not judge a learning program – and by extension the people who designed and developed it – without understanding the context under which it was developed. For example, let’s say I present you with two compliance elearning programs to evaluate.

- The first is a story-driven program that tells the story of Bob, a new employee. It uses rich visuals and animations as it follows Bob along his workday and presents scenarios with compliance concerns. It explores the ramifications of decisions and actions Bob takes for each scenario. It’s also contextual, knowing the role of the person taking the course, so that the learner is only presented with information related to their role.

- The second is mostly text-based, with a few interactions. It covers the policies of the company, common mistakes that are made, and ends in a multiple choice test.

Which program is better? Which was built by the stronger instructional designer? Which one better met the organization’s compliance needs?

Here’s the thing. You don’t have enough information to answer those questions. Let’s add some context reexamine these questions.

- Both of these programs were developed to address the same organizational need. There was a major change in governmental regulation that changed a number of the policies and procedures for front-line employees. There was little notice of these changes; they became effective less than two weeks after they were announced. Senior Management contacted the L&D group and explained that these changes needed to be communicated to affected employees in advance of the regulation taking effect.

- The story-driven program was a much deeper learning experience. It was delivered three weeks after the regulation took effect, and during that time there were two regulatory violations resulting in fines. The project also booked unexpected budgetary expenses for external graphic design development.

- The text-based “page turner” was a much weaker learning experience. It addressed the need of making employees aware of the regulatory changes in advance of them taking effect. It did not result in unexpected budgetary expenses.

Now, let’s look at those questions again.

Which program is better? Which was built by the stronger instructional designer? Which one better met the organization’s compliance needs?

Let me throw in a fourth question – Which scenario do you think pissed off the L&D Manager’s boss?

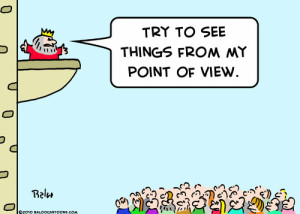

The Differences Between External and Internal Points of View

I’ve worked both internally and as a consultant/freelance developer. These are two VERY different worlds. In fact, I’ve served both roles for the same organization. There are always constraints to work with on a project. The simple fact is that there are usually fewer constraints in place when a project is outsourced then when it is developed in-house.

I’ve worked both internally and as a consultant/freelance developer. These are two VERY different worlds. In fact, I’ve served both roles for the same organization. There are always constraints to work with on a project. The simple fact is that there are usually fewer constraints in place when a project is outsourced then when it is developed in-house.

When I worked internally for the organization I mentioned, I needed to work within the constraints of daily business. I would always negotiate as best I could to create quality learning experiences, but ultimately I was addressing a business need, not a learning need. Many instructional design projects are not everything they could be because of the constraints of what can be based on limited budget, time, or skill set.

These constraints still exist for external development houses and consultants, but they are almost always more relaxed. I still provide occasional design and development support to the organization I worked for. Any time they call me for help, they have already made a few important decisions about the project scope:

- The project requires a development skill set beyond what is available internally

- The project has a higher budget than the norm

- The project is on some level “more important”, and therefore quality is getting more attention than speed or cost-savings

Any time I am contacted for assistance from this organization, those decisions are already in place. As such, it raises the ceiling I have to work with in terms of the level of quality I can deliver while still operating within the project scope. Much like a Subject-Matter-Expert that has forgotten what it was like to be a novice, many external experts have forgotten what it is like to work internally, and are therefore judging projects using criteria that are not applicable in the internal practitioner’s world.

“Best Practices” Vs “Right and Wrong”

As I said earlier, I love when people share great examples of the possibilities that exist for learning programs. There are a number of experts that share their work as examples of industry best practices, and we should thank them for that. Best Practices give professionals a standard to strive for.

Let’s just stop saying that not meeting the standards of “best practice” is somehow “wrong”. Part of applying best practices is the ability to adapt best practices to current conditions. That’s not lowering the bar, that’s adjusting the bar to the current reality.

Be Your Own Yardstick, and Adjust it Accordingly

Be Your Own Yardstick, and Adjust it Accordingly

If there was a scale that measured the quality of a learning experience, the examples and best practices shared by experts would be all the way to the right, near the top of the quality scale. When they share their work, they provide examples that truly define the ceiling of quality we should all be aware of. It provides an excellent margin for comparison as we all try to improve the quality of our work, but it does not provide an all-encompassing standard for judging the work of others.

There are too many variables (level of design/development skill, company culture, available resources, etc) in play to say that any one standard should be applied to all. What IS important is understanding the various levels of quality that can exist, and where the programs you are developing land on that scale.

Being aware of best practices helps us understand what is possible, but it’s not the yardstick you should use to judge your work. Instead, judge yourself on the work you did last week, last month, and over the last few years (if applicable). What’s really important is that you are continually moving forward, building your skills and striving to make each program you build better than the last.